The Vanished World

Presentation of the important out-of-print book by Roman Vishniac by Alberto M. Melis.

In her extraordinary book Das Foto schaute mich an, Katja Petrowskaja publishes a photo from 1930, taken in Gdansk and entitled Mira goes to school. Mira, a 6-year-old Jewish girl, is holding a bag of sweets and has a smile on her face. A dozen years later, probably losing all smiles, Mira is in the Warsaw Ghetto and receives ninety photos from her father, including her own, with the task of saving them, whatever happens. Mira hides the 90 photos at the bottom of her tin mess. And the pictures in the mess room, together with Mira, go through the years and the horrors of the concentration camps of Bliryn-Majdanek, Auschwtz-Birkenau, Hinderburg, Gleiwitz, Mittelbau-Dora and Bergen Belsen. And incredibly, together with her, they survive.

Mira's father, Moritz Ryczke, was also saved from the Holocaust. But of all the other relatives and friends, what remained were only those 90 photographs. "For some of those people," writes Katja Petrowskaya, "they will be the only proof of their existence."

The incredible journey of Mira's 90 photos cannot help but remind us of another somewhat similar story, albeit on a larger scale. The one that saw the young Jewish photographer Roman Vishniac, take and rescue thousands of photographic images of an entire world destined to disappear at the hands of the Nazis.

Vishniac, born in 1897 in Russia and emigrating with his family to Berlin during the Bolshevik revolution, was not a professional photographer, much less a documentary photographer. He was an eclectic scholar of art, medicine, zoology, and biology who experimented with photography under a microscope and dabbled in street photos.

It was probably the images taken on the streets of Berlin during the years of Hitler's rise that attracted the attention of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC), a Jewish relief organization in New York.

The JDC asked Vishniac in 1935 to document the lives of Jews, especially poor Jews, in Central and Eastern Europe. And Vishniac, with his Leica, his Rolleiflex, and a Latvian passport obtained thanks to the union with his wife Luta Bagg, began a series of trips, pretending to be a textile merchant. From 1935 to 1939, he managed to cross Poland, Czechoslovakia, Romania, and Lithuania. He encountered many difficulties (including a dozen arrests), but managed to take a total of twelve thousand photos, the negatives of which he carefully developed and hid in Berlin, for fear that the Nazis would take over his work.

A work that was, literally, extraordinary. Both from a documentary point of view, aimed at testifying for the JDC the precarious economic conditions of the Jews in Eastern Europe, so that they can send them aid of different kinds. Both from a historical point of view. Because almost all the people portrayed by Vishniac, along with their communities, very soon faced total destruction. An entire world, with its shtetels, its traditions, its crafts, its language (Yiddish) and its ancient Ashkenazi culture, which in a few years was entirely devoured by the Shoah.

To understand how Vishniac's work was anchored in the tragic reality of things, just think of the importance that his photos had at the end of 1938. The Nazis arrested thousands of Jews of Polish descent in Germany and forcibly transported them to the Polish border. The Polish authorities did not accept them and about 9,000 people, including children, pregnant women, the elderly and the infirm, were trapped in the small town of Zbaszyn, in desperate conditions. Vishniac managed to sneak into the barracks of the deportees, for two days he took photos, managed to escape fortunately and sent the images, as well as to the League of Nations, to the JDC. Which, responding promptly, sent economic aid and managed to build an equipped refugee camp in Zbaszyn. It was a single photo of Vishniac, that of the little Nettie Stub who later became famous, that probably saved the life of the little girl and her family, who were rescued by the Red Cross.

When the situation of the Jews in Germany became unbearable, Roman Vishniac managed to get his wife and two children to emigrate to Sweden and then reached France. Where, however, he was arrested by Marshal Pétain's police and interned at Camp du Ruchard, in Indre-et-Loire. Freed, he finally reached the United States, managing to bring with him the negatives of only 2000 photos, which he hid in the linings of his clothes. The others remained hidden under the floor of a house in Clermont Ferrand, in central France, where his father hid until the end of the war. Part of this photo was then returned to Vishniac, via Cuba, by his friend Walter Bieber.

In his early years in the United States, Vishniac tried in vain to draw attention to the extremely precarious conditions of the Jews of Central and Eastern Europe. He wrote and sent a few photos to President Roosevelt and his wife Eleanor, inviting them to one of his exhibitions, but without success. It was only in 1947, at the end of the war, when Vishniac published the book The Vanished World: Jewish Cities, Jewish People, that the testimonial importance of his work began to be understood.

Second life in the United States.

In his second life away from Europe, Roman Vishniac, who died in New York in 1990, continued to stand out for his eclecticism. A research associate at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine and a professor of biological education, art collector, scholar of Judaism and convinced Zionist, he continued to practice photography in very different ways, from street photography, reportage, microphotography, nature photography and portraiture. His portraits of Albert Einstein and Marc Chagall became famous. He garnered an impressive amount of accolades, his books had international distribution, and in 2018, his daughter Mara donated her father's entire work to the Magnes Collection at the University of California, Berkeley.

Nevertheless, Vishniac's work, and in particular that fundamental segment represented by the photos taken in Europe on the eve of the Second World War, was not spared from criticism, largely based on nothing. Vishniac took his photos on the streets and in places where Jews gathered, private homes, schools, markets, synagogues, often taking them as quickly as possible and covertly. The criticisms of the repetitiveness of the shots were therefore completely surreal, as if Vishniac had had the faculty to create at will scripts that were always different from the reality he encountered on his path. Just as the criticism of the formal and compositional aspect of his photos was bordering on the ridiculous, with hands, feet and heads "popping out everywhere". Exactly as often happens today to any street photographer who practices in difficult conditions, with the difference that in those times the possibilities of intervening in post-production were limited to stratagems in the darkroom.

Another, more recent criticism levelled at Vishniac was the recurring discrepancy between the photos and their captions. Which errors were discovered in the descriptions, dates, and places indicated. To the point that today, several of his photos exhibited in museums and in the most important US collections have captions indicating different possible shooting locations. But even this defect, if it is a defect, is actually justified by the difficult conditions in which Vishniac worked and then saved his work. In short, it is challenging to be able to keep thousands of negatives hidden for years in the most disparate places in order. Just as it was almost impossible to memorize exactly every single shot taken in the dense interweaving of small towns, towns, paths and roads of the nations crossed.

For our part, faced with the beauty and extraordinariness of Roman Vishniac's photos, we just have to observe them with a new sensitivity. Letting every single photo interact with us and with our ability to interpret the narrative fragments of this world and this vanished humanity. Even with that slowness that Katia Petrowskaja suggests in her book, in which every single photo "speaks to her": a dilated attention and time that are the same as that needed analogue photography, in all its darkroom processes.

Alberto M. Melis

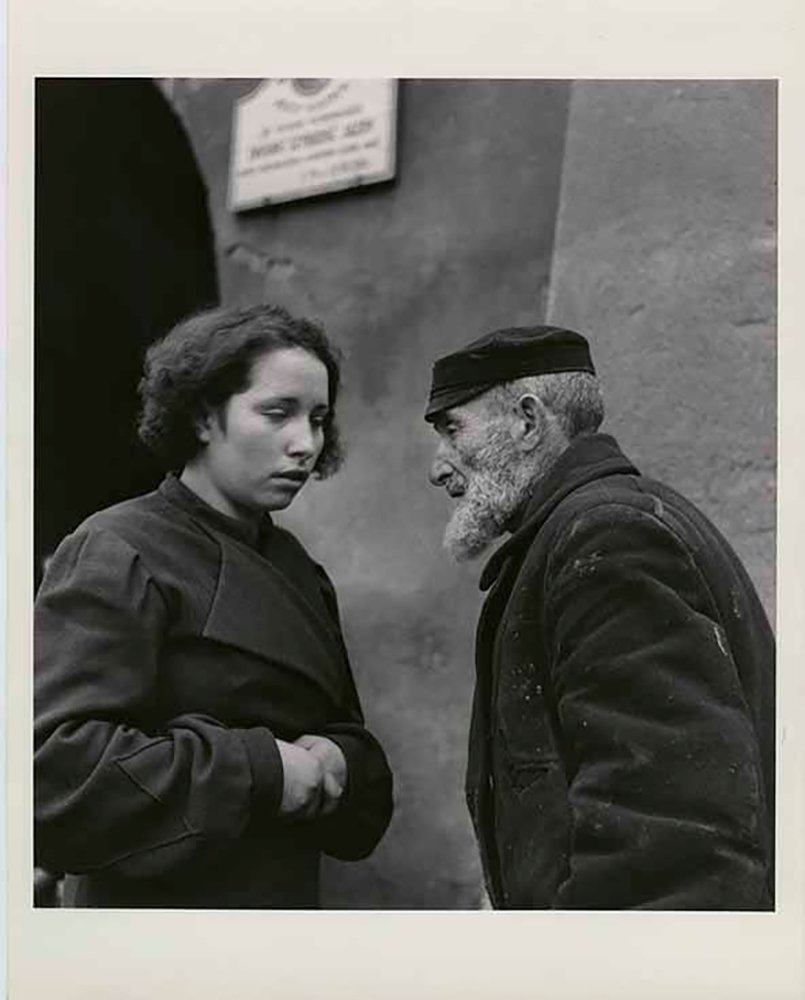

An elder of the village, Vysni Apsa

Nettie Stub at Zbaszyn 1938

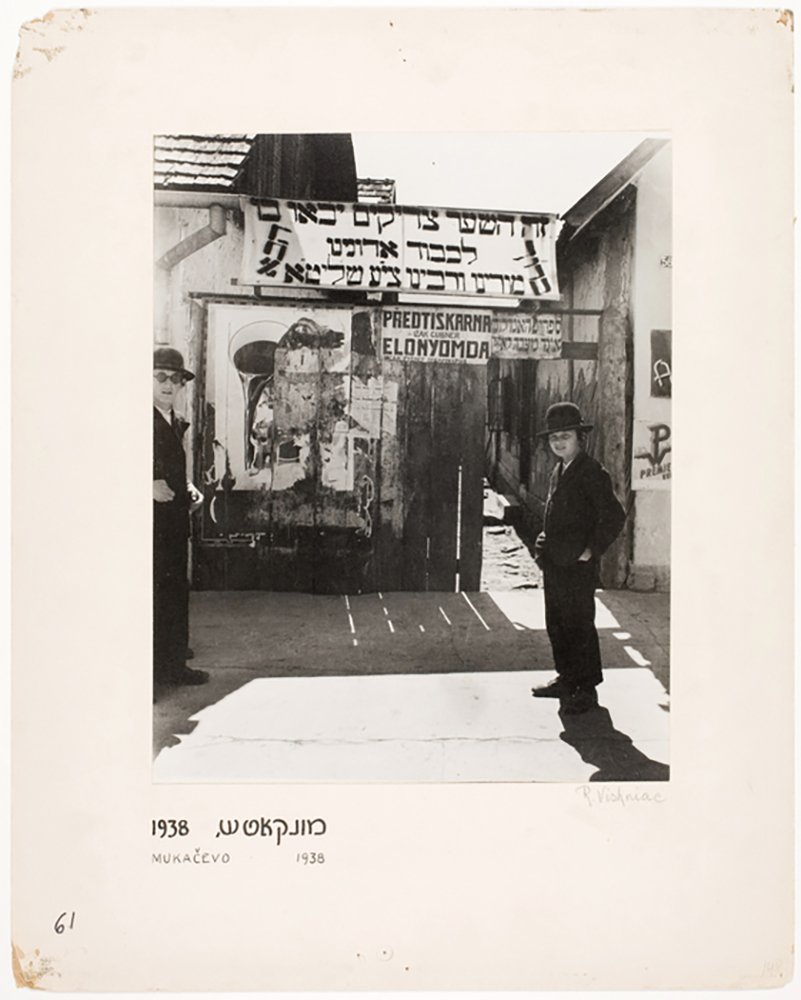

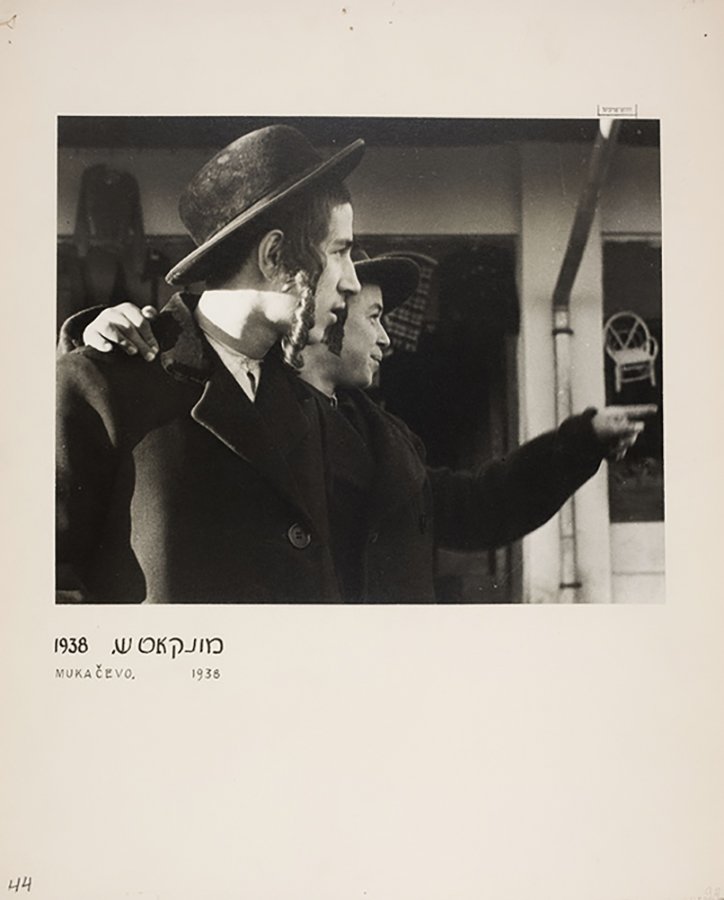

Mukačevo 1938

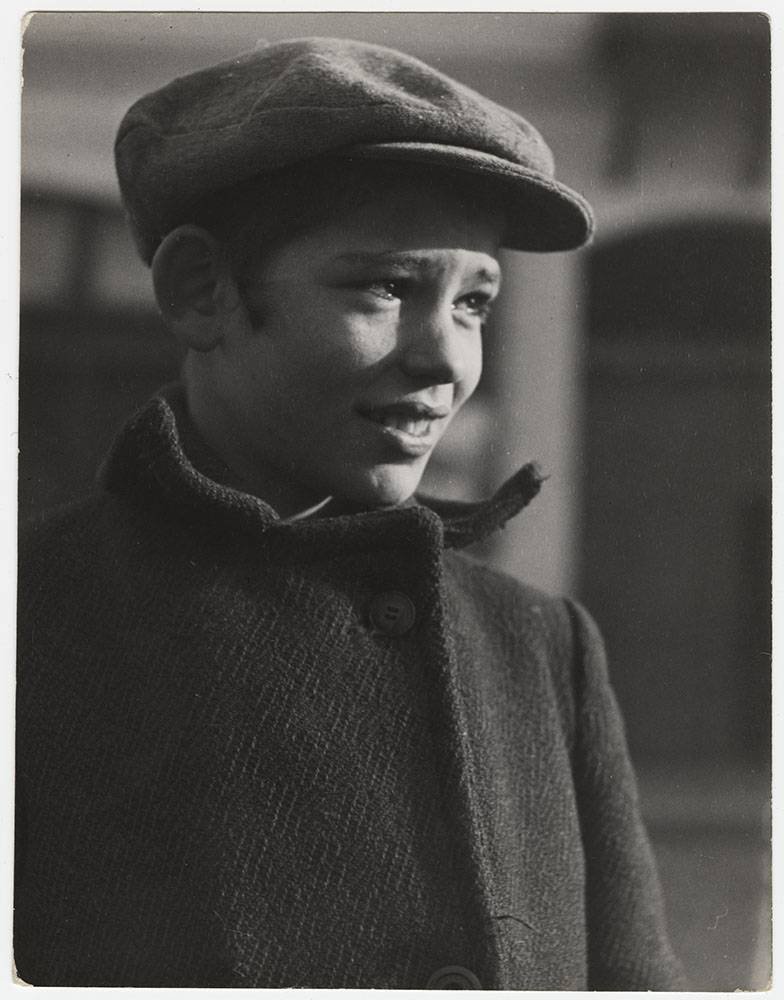

Warsaw 1937

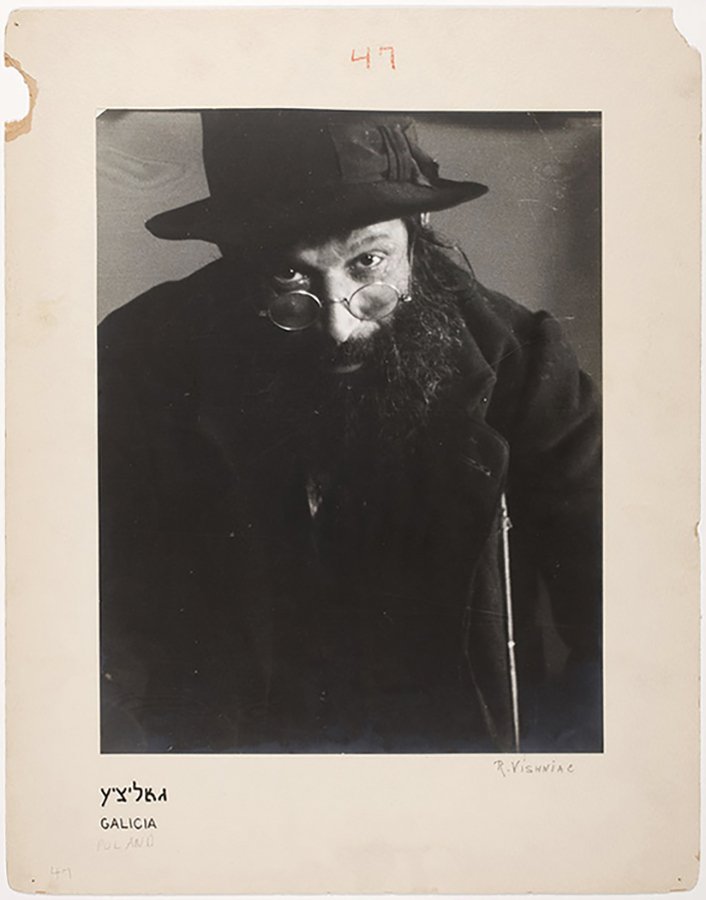

Hasidic man, Krakow 1938

Trnava 1937

Beggar standing outside Jewish printing shop during the Polish antisemitic boycotts, Lask

A Family of Bagel Peddlers, Warsaw, 1938

Lodz or Warsaw

Chaim Simcha Mechlowitz, a farmer and tanner, Vysni Apsa, Carpathian Ruthenia. ca. 1938

Cattle trader in the open market, Chust, Carpathian Ruthenia

Uzhorod 1937

A boy clutching his satchel, Pabianice

Basement home of a porter and his family, Warsaw

1937 Vrchni Apsa

Slonim 1937

Carpathia 1938

Woman carrying metal buckets, Wilno

Teacher and students in cheder Jewish elementary school, Slonim 1938

students waiting in line for the mikveh (ritual bath), Carpathian Ruthenia

Slovakia 1935

Mukachevo, 1938

Jewish refugee, detention camp in Zbaszyn

Mukachevo

Mukacevo 1938

Warsaw 1937

After morning services on the Sabbath, Kazimierz, Krakow 1938

Yumi Ostreicher, a student in the yeshiva of Rabbi Baruch Rabinowitz, Mukacevo

Young girl returning from the store with a pot of soup and a bottle of milk, Lodz 1938

Grandfather granddaughter_Warsaw 1938

Yeshiva students, Mukacevo

Krakow 1938

Vendor selling apples on Gesia Street, one of the main thoroughfares in a Jewish district of Warsaw 1937

Sara, sitting in bed in a basement dwelling, with stenciled flowers above her head, Warsaw

Mukacevo 1937

Warsaw 1938

Warsaw 1938

Malnourished child eating a crust of bread in the TOZ (Society for Safeguarding the Health of the Jewish Population) summer camp in Otwock, near Warsaw

Enterance to Kazimierz, the Jewish district of Krakow 1937

Children seeking light and air outside their basement home, Krochmalna Street, Warsaw 1938

Man purchasing herring, wrapped in newspaper, for a Sabbath meal, Mukacevo

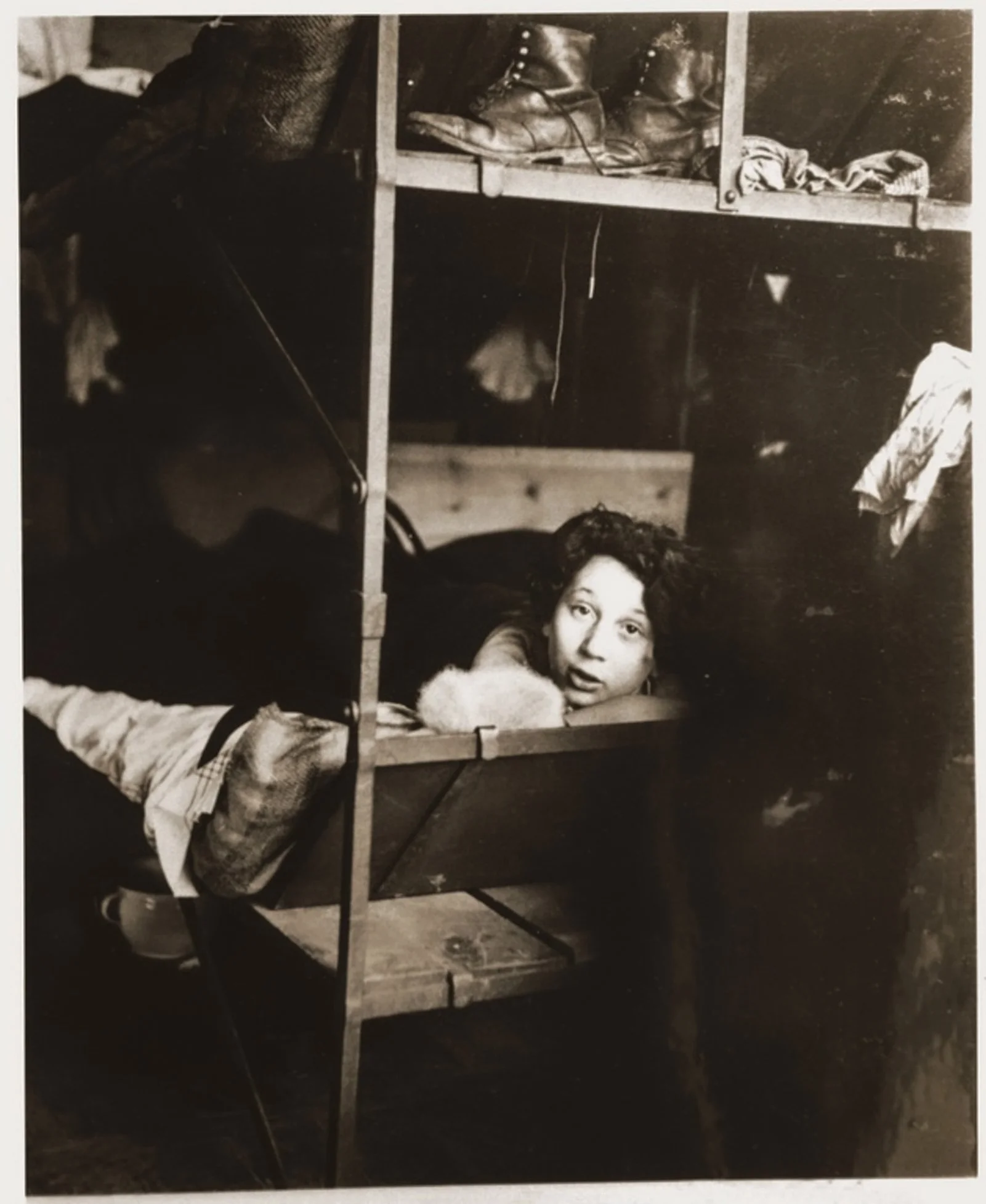

Jewish refugees in horse stables that have been converted to living quarters, detention camp in Zbaszyn, 1938

In the synagogue courtyard, Wilno

Chanukah. Kazimierz, Krakow 1938

Mukachevo, 1937