Letter from Seoul - 10

Older than America

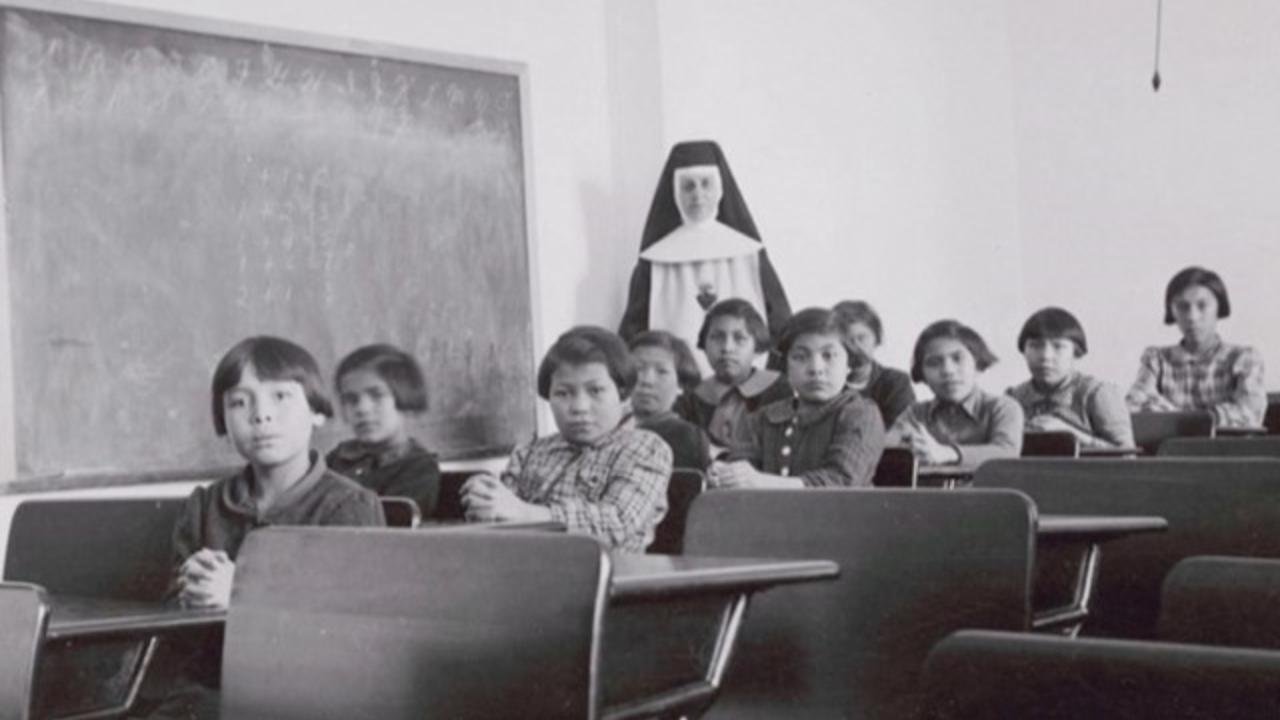

This concerns the U.S. government’s official 150-year policy of trying to destroy Native American culture by “taking away” children from their families for “re-education,” so they would become “good citizens.”

This policy of genocide is old news, not just in the context of American history – but as a de facto policy when one group tries to dominate another group by demonizing the culture of the occupied society. Thought control starts with stripping people of both their language and their core belief system.

The examples throughout history are endless, and the practice continues today with Putin’s attempt to crush Ukraine, Netanyahu’s Nazi-textbook approach to exterminating the Palestinians, and Xi’s similar efforts in the West of China to break the will of millions of Muslim Chinese and make them experience “proper thinking.”

At one time, the Five Civilized Tribes in the American southeast (the Carolinas, Georgia and Florida), included the Cherokee, the Choctaw, the Chickasaws, the Creeks and the Seminoles. They were all told by U.S. government officials that life would be so much better if they simply learned English, embraced Jesus, cut their hair and wore “white man’s clothing.”

A great many of these Native American groups gave it a good try – yet it was never going to be good enough. Ironically, some of the groups became slave owners. Ironic, since the Spanish intended this fate for the indigenous peoples of the Western Hemisphere – but their immunity systems could not handle exposure to European diseases. But the Africans had no such issues, so: “get down in the boat, and row.” African slaves quickly realized that they were not going to land on Plymouth Rock ... but that Plymouth Rock was going to land on them.

The tribe that made the greatest effort to “become white” were the Cherokees. And finally, they put this to the test by attempting to buy property in Georgia – and the concept of owning anything that is part of this planet is still at odds with the belief systems of most every indigenous group in America.

In what is known in American history as Worcester v Georgia (1832), the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Native Americans had the right to buy property. John Marshall, the first chief justice of the U.S. The Supreme Court made this ruling.

Andrew Jackson, the last of the American Presidents born as a British citizen, famously said: “Marshall has made his ruling. Let’s see him enforce it.”

If you have a chance to review any photos of Trump in the White House during his term in office, a large painting of Andrew Jackson is nearly always in the background. There’s a reason. Jackson was a morally bankrupt man, a role model for Trump.

Not only did John Marshall do nothing to challenge Andrew Jackson, “Old Hickory” as the President was known, initiated the forced march of The Five Civilized Tribes across the American South, and across the Mississippi River to Oklahoma Territory – considered worthless real estate until the discovery of oil. See: Killers of the Flower Moon (2023).

This forced march is known as The Trail of Tears, and estimates of the number of people who died on the way to Oklahoma – a Choctaw name that means “Red People,” vary, ranging from 4,000 to 17,000 people. No one knows for certain, since these Native Americans had no standing as people.

Andrew Jackson’s parents both emigrated from Carrickfergus, Ireland in 1767. He grew up in a log cabin in a remote region of the Carolinas, before the territory was divided into two states.

A decade after the Trail of Tears, a group of Choctaw leaders and others met in eastern Oklahoma to raise money for “the relief of the starving poor in Ireland.”

The Choctaw people collected the equivalent of $5,000 by today’s standards to help during the Potato Famine (1847-1851).

Those of us who came of age in the 1960s and mid-1970s were never taught any of this history in either high school or college.

In 1995, Irish President Mary Robinson met with members of the Choctaw Nation in Oklahoma to express her country’s gratitude for the enormous generosity of the gift in 1847 that helped ease the suffering of so many Irish.

The ceremony took place in Tulsa, and it’s the only time in my life that I stood in a receiving line to meet and shake hands with a politician.

There are two women I rely on daily for intelligent dispatches about American politics: Heather Cox Richardson and Joyce Vance. The women are contemporaries, separated in age by two years – with Vance born in 1960 and Richardson following in 1962. Richardson is currently a professor of history at Boston College. To say “Harvard educated” was like a coin of the realm. The school has de-based itself over the years, largely due to Legacy Admissions, a form of Affirmative Action for American patricians. A notable half-wit with a Masters of Business Administration (MBA) from Harvard is George W. Bush. Richardson helps restore some of the shine to a Harvard degree. She is the real deal. Joyce Vance is currently on staff at the Alabama School of Law, and also serves as a MSNBC on-air contributor. Prior to this, she was appointed by President Obama in 2009 to serve as U.S. attorney for the Northern District of Alabama. Vance held the position until 2017, when she decided to accept the role of visiting professor at the Alabama School of Law.

Both Richardson and Vance teach me something new and important every day. Richardson provides the historical context, and Vance offers legal background. Their writing is part of the Substack group, a San Francisco-based platform of daily newsletters. While the two women cover separate specialties (history and law), their values and character are similar. It’s no surprise that they are part of a mutual admiration society, and are often on the same panels.

I offer this as an introduction to Richardson’s newsletter for June 2, which discusses the history of Native American civil rights in the U.S.

Today is the one-hundredth anniversary of the Indian Citizenship Act, which declared that “all non-citizen Indians born within the territorial limits of the United States be, and they are hereby, declared to be citizens of the United States: Provided, That the granting of such citizenship shall not in any manner impair or otherwise affect the right of any Indian to tribal or other property.” click the button

"Wandering Stars" by Tommy Orange is the highly anticipated sequel to his award-winning novel "There There." The story unfolds in two timelines. The first is set in Colorado in 1864, following the aftermath of the Sand Creek Massacre, and the establishment of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School. The second timeline is set in Oakland in 2018, focusing on a family struggling to cope with the aftermath of a shooting. Tommy Orange weaves together these narratives, delivering a poignant and powerful exploration of sorrow, rage, and hope.

Tommy Orange is a recent graduate from the MFA program at the Institute of American Indian Arts. He is a 2014 MacDowell Fellow and a 2016 Writing by Writers Fellow. He is an enrolled member of the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma. Tommy was born and raised in Oakland, California, and currently lives in Angels Camp, California.

In that bygone era of grade school, when a collection of students was together in the same room with the same teacher for an academic year, my sixth-grade teacher bought us all a smart looking paperback copy of Roget’s Thesaurus. If he had handed me a bag of gold, it would not have been as valuable as that 50-cent thesaurus. It changed my life.

For high school graduation, my mother presented me with a portable manual typewriter and a hardbound copy of Roget’s Thesaurus. I’ve had a half-century relationship with that edition – longer than my connection with any one person, and it has accompanied me from St. Louis-to-Seoul, and all points in between. That edition from 1970 remains an integral part of my book collection.

Allegedly, Christopher Hitchens (1949-2011), an immensely talented wit and writer, could imbibe liberal quantities of alcoholic refreshments throughout the day, hold forth with ease and intellectual dexterity on literary, political and religious issues at both formal lectures and lively parties - then sit before a keyboard at 1 a.m. and produce a stunning essay for Vanity Fair that marked him as the rightful heir to Gore Vidal in his prime.

I’m still waiting for lightning to strike, to know what I want to be when I grow up, to be enraptured by a muse who will inspire me as much as June Mansfield (1902-1979) shaped the life of Henry Miller (1891-1980), her husband, who went unaccompanied to Paris in 1930 and during this down-and-out period wrote countless letters to his wife and friends in New York City that became the material for the scandalous Tropic of Cancer – banned as obscene for 30-years, edited by his mistress and benefactor, Anais Nin (1903-1977). Perhaps the best we can do is to be an interesting collection of contradictions.

Call me Kennedy. Ahab had his whale. William Burroughs (1914-1997) had his heroin. Bruce Chatwin (1940-1989) had his Patagonia. As for me, I have a camera and a passport.

The play’s the thing.

Michael Kennedy