Mercoledì 5 ottobre

For over 35 years, the American/British photographer Richard Bram has been walking the streets of the world in search of the special moments of everyday life. He has worked on large public events and intimate private moments, always looking for the significant gesture to animate his photographs. His approach is straight: In black & white or color, he doesn't set up a photo or alter the scene. The photograph is either there or it is not.

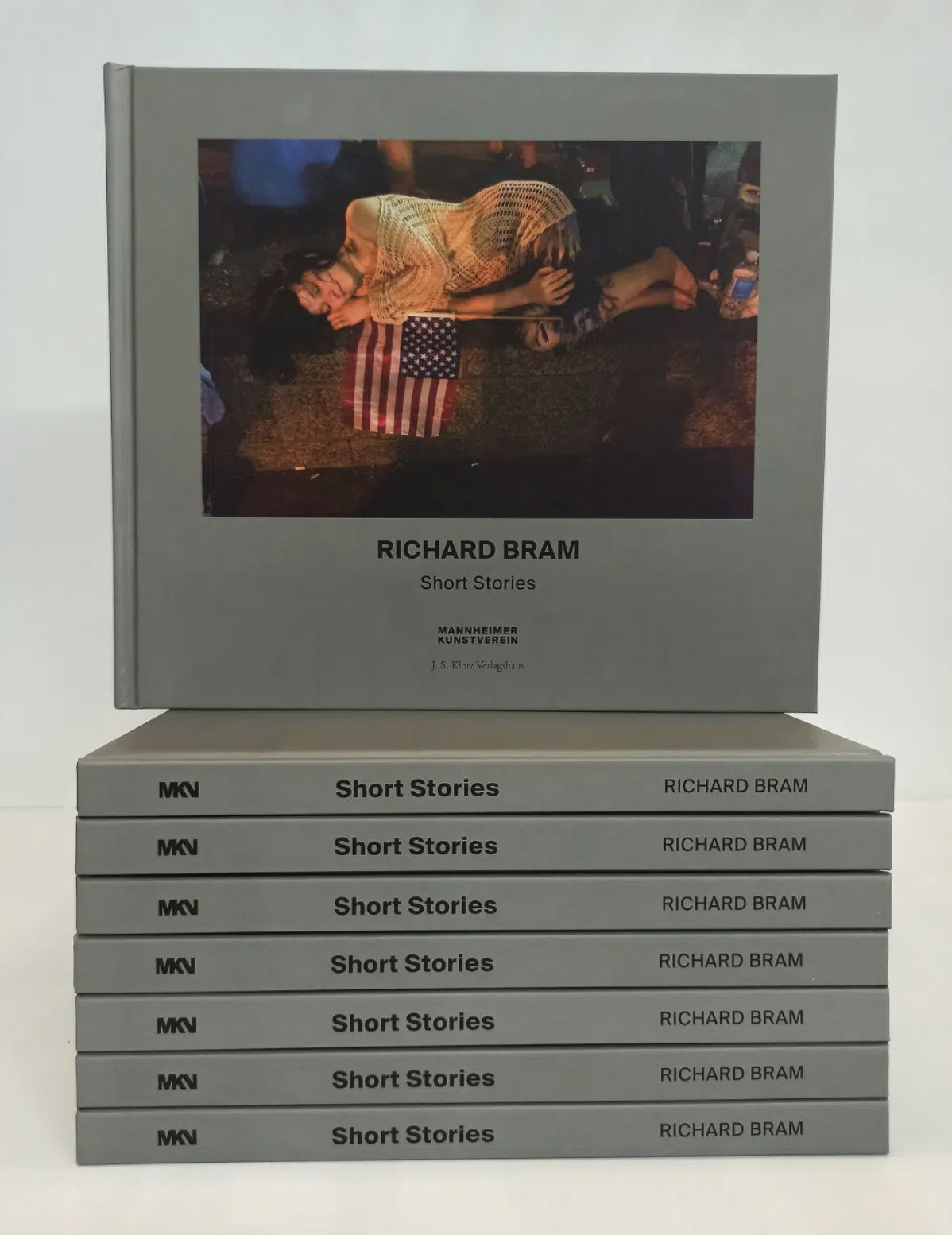

Born in Philadelphia, USA, in 1952, Bram has been a professional photographer since 1984. He was a founding member of in-public, now UP Photographers, the first international street photography collective. In addition to being regularly published in traditional and digital magazines, he regularly writes and lectures on street photography. Today, based in London, he hopes to be on the move again soon in search of new images. Three books of his work have been published, "Richard Bram: Street Photography" (2006), “Richard Bram: NEW YORK” (2016) and “Short Stories” (2020). In 2020, Bram received the honor of a major retrospective exhibition at the Mannheimer Kunstverein of Mannheim, Germany. His work has been seen in over forty solo and group exhibitions around the world, and is part of major museum collections in America and Europe. He now makes his home on the banks of the River Thames in east London where he observes the water, light and air of that great river.

Da oltre 35 anni il fotografo americano/britannico Richard Bram cammina per le strade del mondo alla ricerca dei momenti speciali della vita quotidiana. Ha lavorato a grandi eventi pubblici e intimi momenti privati, sempre alla ricerca del gesto significativo per animare le sue fotografie. Il suo approccio è diretto: in bianco e nero oa colori, non allestisce una foto né altera la scena. La fotografia o c'è o non c'è.

Nato a Filadelfia, negli Stati Uniti, nel 1952, Richard Bram è un fotografo professionista dal 1984. È stato membro fondatore di in-public, ora UP Photographers, il primo collettivo internazionale di street photography. Oltre ad essere pubblicato regolarmente su riviste tradizionali e digitali, scrive e tiene conferenze. Sono stati pubblicati tre libri del suo lavoro, 'Richard Bram: Street Photography' (2006), 'Richard Bram: NEW YORK' (2016) e 'Short Stories' (2020). Nel 2020 Bram ha ricevuto l'onore di una grande mostra retrospettiva al Mannheimer Kunstverein di Mannheim, in Germania. Il suo lavoro è stato visto in oltre quaranta mostre personali e collettive in tutto il mondo e fa parte delle principali collezioni museali in America e in Europa. Ora vive sulle rive del Tamigi, East London, dove osserva l'acqua, la luce e l'aria del grande fiume.

Interview by Batsceba Hardy

Ciao Richard, grazie per essere qui con noi, tu che sei uno dei simboli della street nel mondo. A questo proposito, io credo che tu sia proprio uno dei fotografi che meglio rappresenta lo spirito della street: raccontare storie in uno scatto. È quello che sta alla base di molte scelte di Progressive! Vuoi parlarci di questo? Devo anche averlo letto in qualche intervista.

Quello che sembra sempre muoverti è la sincerità dello scatto. Non cerchi di mascherare i risultati con l’esasperazione dei colori e nemmeno con la tecnica che va oggi per la maggiore del chiaroscuro. Questa scelta è durata mezzo secolo, non hai mai avuto tentazioni manipolatorie?

In una delle tue prime foto (“Louisville 1986”) si vede Muhammad Alì che firma un autografo per due bambine. In una delle tue ultime foto, invece, hai ripreso un paesaggio deserto, avvolto dalla nebbia del mattino. Vuol dire che stai andando verso un paesaggismo pittorico, una realtà totale, più disincarnata, senza figure?

Nel tuo libro Short Stories, il catalogo dell'esposizione al Manneheimer Kunstverein, pochi sono i soggetti sorridenti. Gli uomini e le donne ritratti sono imbronciati, distratti, chiusi in se stessi. Si può dire che tu vuoi rappresentare l'alienazione moderna?

Infatti ci sono sempre figure al centro delle tue fotografie, ma molti dei titoli fanno riferimento a cose (umbrella, parasol, taxi, poster, Blackberry phone, ecc.). In una foto “italiana”, addirittura l'attenzione è spostata dal soggetto umano al frontale di una “500”, la piccola utilitaria Fiat.

Hai chiamato alcune tue serie in base al colore, “rosa”, “rosso”, “giallo”, ecc. Puoi spiegare il perché?

Sei stato testimone anche di movimenti di protesta sociale come “Occupy Wall Street”. Credi che la fotografia possa contribuire alla rivoluzione delle coscienze? E se sì, in che modo può farlo?

Hi Richard, thank you for being here with us, especially as you are one of the well known symbols of street photography in the world.

In this regard, I believe that you are one of the photographers who best represent the spirit of the street: telling stories in one shot. That's what underlies many of Progressive's choices! Do you want to tell us about this?

Having read some of your previous interviews I understand what always seems to move you is the sincerity of the shot. You do not try to mask the results with the exaggeration of colours or even with the technique of "chiaroscuro", that is now so popular. You have operated this way for the last half a century, have you never had any temptations to manipulative your images or methods?

In one of your first photos (“Louisville 1986”), Muhammad Ali is seen signing an autograph for two little girls. In one of your latest photos, however, you have taken a desert landscape, wrapped in the morning fog. Does it mean that you are moving towards a pictorial landscape, a total reality, more disembodied, without figures?

In your book Short Stories, the catalogue of the Mannheimer Kunstverein exhibition, there are only a few smiling subjects. The men and women portrayed are generally sulky, distracted, and withdrawn. Can it be said that you want to represent modern alienation?

Although there are often figures in the centre of your photographs, many of the titles refer to things such as an umbrella, parasol, taxi, poster, Blackberry phone, etc. In an “Italian” photo, even the attention is shifted from the human subject to the front of a “500”, the small Fiat compact city car.

You have chosen to name some of your series with colours, 'pink', 'red', 'yellow', etc. Can you explain why?

You have also witnessed social protest movements such as 'Occupy Wall Street'. Do you believe that photography can contribute to the revolution of conscience? And if so, how?

In this regard, I believe that you are one of the photographers who best represent the spirit of the street: telling stories in one shot. That's what underlies many of Progressive's choices! Do you want to tell us about this?

One of the differences between street photography and more traditional documentary and photojournalism photography is just that: Getting it all in one rather than relying on a longer narrative or accompanying text to fill in the details. We – or at least I – am trying to record the moment that happens in front of me and nothing more. This doesn’t mean that there isn’t multi-photo work in our genre – Elliot Erwitt comes quickly to mind - but that’s the challenge for the street photographer, and what makes really good street pictures so difficult to get.

When we look at this sort of photograph, all we have is what is in the rectangle. There is no sound, no before or after, and we know nothing to the right or left. It all has to be there without words. If, when looking at one of my photographs, you begin to construct a story in your mind around it, I’ve succeeded. A friend teaches film writing and uses a few of my photographs in her course. She says “Here is the film still. Write the rest of the scene.” The variations are endless.

Having read some of your previous interviews I understand what always seems to move you is the sincerity of the shot. You do not try to mask the results with the exaggeration of colours or even with the technique of "chiaroscuro", that is now so popular. You have operated this way for the last half a century. Have you never had any temptations to manipulative your images or methods?

Not really. I’ve almost always been a straight photographer. If I recorded the image on black-and-white film, that’s how it stays; if I recorded it in colour, in the final product I want to see what it looked like to me when I clicked the shutter.

I’ve always used colour in my work as a public relations and public event photographer but kept making my personal work in black and white for a long time. But in 2010 I made the conscious decision to focus on making my personal work in colour. I found out very quickly that colour is much harder to do well.

You’re right – there is a fashion at the moment for intense colours and deep blacks, all in high contrast. There’s nothing wrong with that approach and there are a lot of fine photographs and photographers working this way. For example, looking at my Australian friend Trent Parke’s colour work, there are those intense colours from that strong southern sun combined with extraordinary moments in the street scene. Narelle Autio and my UP Photographers colleague Jesse Marlow also amaze me constantly with the images they make.

Intense colour is seductive, almost a drug. There is a risk to this: producing the look without content, and most of my work and that of the photographers I admire most have the emotional content as well. The best photographs ask more questions that they answer and elicit more than one emotion from the viewer. If it’s all about colour blocks that’s fine, but as a mass, it’s just not enough for me.

In one of your first photos (“Louisville 1986”), Muhammad Ali is seen signing an autograph for two little girls. In one of your latest photos, however, you have taken a deserted landscape, wrapped in the morning fog. Does it mean that you are moving towards a pictorial landscape, a total reality, more disembodied, without figures?

You are referring to my current and continuing series “Limehouse Reach.” I’ve never thought of myself as a landscape photographer, and have always said that I’d rather sit in the landscape and contemplate it than try to put it into a little rectangle.

But in late 2016 we left New York and moved to our home on the River Thames in London. I was immediately awed by the ever -changing light, air, and water of the river. What can I say? I’m a photographer and for the first time in my life began a study of the landscape in front of me every day – and every night. I’m particularly drawn to fogs, mists, storms, clouds, and twilight rather than bright sunlit days. They are more transient and fleeting and harder to photograph. I’m also inspired by the many painters I studied in university, particularly Turner and Whistler who actually sketched and painted within a hundred meters of where we live, and Constable who was also drawn to the dramatic skies over England.

In your book Short Stories, the catalogue of the Mannheimer Kunstverein exhibition, there are only a few smiling subjects. The men and women portrayed are generally sulky, distracted, and withdrawn. Can it be said that you want to represent modern alienation?

This is because that’s what most of us look like on the street. We are drawn into ourselves as we go from one place to another. People are certainly laughing and smiling but in general they are not. I photograph what I see. I don’t know if I am representing anything more than that. At the most, my choices are determined by my own mood at that moment. All of us reveal our psychological states in our work. Perhaps not in any one photograph, but if you look at a mass of photographs made by one person in a particular period, you’ll see what’s going on in their head.

For example, about three months after I’d moved to London in 1997 my friend, the photographer Susan Lipper was in town and we got together. I brought along my recent contact sheets for her to see. She went through them and said “Richard, there are some very good images here, of course, but mostly what I’m getting is distant, angry, and alienated.” I said “yeah – that about sums it up.”

Although there are often figures in the centre of your photographs, many of the titles refer to things such as an umbrella, parasol, taxi, poster, Blackberry phone, etc. In an “Italian” photo, even the attention is shifted from the human subject to the front of a “500”, the small Fiat compact city car.

The titles are almost always completely unimportant in my photographs. Their only purpose is to differentiate them from another photograph taken in the same place.

I find titles almost always heavy-handed and useless with street photographs. Most of the time they actually limit what I take away from the photograph by choking it in a web of words.

You have chosen to name some of your series with colours, 'pink', 'red', 'yellow', etc. Can you explain why?

Same answer as above. If I made ten photographs at the Easter Parade in New York, I want to differentiate them in my own mind with simple tag. With colour photographs, if there is one predominant object of a certain colour, like a yellow coat, pink suit, or red tie, that’s the tag.

You have also witnessed social protest movements such as 'Occupy Wall Street'. Do you believe that photography can contribute to the revolution of conscience? And if so, how?

I’m not really sure. Certainly the fact that everyone has a still/video camera in their pocket today has changed the way we see police and justice. The open murder of George Floyd by a policeman would have gone unseen and unpunished if it had not been recorded by a strong woman with her iPhone recording the whole thing. This is now happening all over the world as those who perpetrate violence and injustice can’t pretend that it didn’t happen or that it was the victim’s fault. The worldwide Black Lives Matter movement would not have happened without this. It is much harder for ordinary people to pretend that everything is fine and that this isn’t happening all the time.

But an individual photograph? I’m much less sure. When I think back to the 1960s (yes, I am very old and remember them well) there were a few incredible photographs that stay in my mind from the Viet Nam war and the protests against it. The naked child running from her burning village of My Lai, and conversely the student woman in shock and horror over the body of a dead protesting student murdered by a nervous National Guardsman in Ohio. More recently, We all know the photograph of the young man carrying shopping bags standing in front of the tanks in Tien An Men Square in Beijing. But did this stop the massacre that happened that night or the murder of thousands when the movement was crushed? There are many other single images that stay with us, but will they change to world? I’m sorry to say that I do not think that they will.

A questo proposito, credo che tu sia uno dei fotografi che meglio rappresenta lo spirito della strada: raccontare storie in uno scatto. Questo è ciò che sta alla base di molte delle scelte di Progressive! Vuoi parlarci di questo?

Una delle differenze tra la fotografia di strada e la fotografia documentarista e il fotogiornalismo più tradizionale è proprio questa: ottenere tutto in uno piuttosto che fare affidamento su una narrazione più lunga o sul testo di accompagnamento per riempire i dettagli. Noi, o almeno io, stiamo cercando di registrare il momento che mi accade davanti e niente di più. Questo non significa che non ci sia lavoro multi-foto nel nostro genere – mi viene subito in mente Elliot Erwitt – ma questa è la sfida per il fotografo di strada, e ciò che rende così difficili ottenere foto di strada davvero buone.

Quando guardiamo questo tipo di fotografia, tutto ciò che abbiamo è ciò che è nel rettangolo. Non c'è suono, né prima né dopo, e non sappiamo nulla a destra oa sinistra. Tutto deve essere lì senza parole. Se, guardando una delle mie fotografie, inizi a costruire una storia nella tua mente attorno ad essa, ci sono riuscito. Un'amica insegna scrittura cinematografica e usa alcune delle mie fotografie nel suo corso. Dice “Ecco ancora il film. Scrivi il resto della scena. Le variazioni sono infinite.

Leggendo alcune tue precedenti interviste capisco che quello che sembra sempre commuoverti è la sincerità dello scatto. Non si tenta di mascherare i risultati con l'esagerazione dei colori e nemmeno con la tecnica del 'chiaroscuro', che ormai è tanto in voga. Hai operato in questo modo nell'ultimo mezzo secolo. Non hai mai avuto tentazioni di manipolare le tue immagini o i tuoi metodi?

Non proprio. Sono quasi sempre stato un fotografo “diretto”. Se ho registrato l'immagine su pellicola in bianco e nero, è così che rimane; se l'ho registrato a colori, nel prodotto finale voglio vedere com'era quando ho premuto l'otturatore.

Ho sempre usato il colore nel mio lavoro di fotografo di pubbliche relazioni e di eventi pubblici, ma ho continuato a realizzare i miei lavori personali in bianco e nero per molto tempo. Ma nel 2010 ho preso la decisione consapevole di concentrarmi sulla realizzazione del mio lavoro personale a colori. Ho scoperto molto rapidamente che il colore è molto più difficile da fare bene.

Hai ragione, al momento c'è una moda per i colori intensi e i neri profondi, tutti ad alto contrasto. Non c'è niente di sbagliato in questo approccio e ci sono molte belle fotografie e fotografi che lavorano in questo modo. Ad esempio, guardando il lavoro a colori del mio amico australiano Trent Parke, ci sono quei colori intensi di quel forte sole del sud combinati con momenti straordinari nella scena di strada. Anche Narelle Autio e il mio collega UP Photographers Jesse Marlow mi stupiscono costantemente con le immagini che realizzano.

Il colore intenso è seducente, quasi una droga. C'è un rischio in questo: produrre lo sguardo senza contenuto, e la maggior parte del mio lavoro e quello dei fotografi che ammiro di più hanno anche il contenuto emotivo. Le migliori fotografie pongono più domande a cui rispondono e suscitano più di un'emozione da parte dello spettatore. Se si tratta solo di blocchi di colore va bene, ma come massa, non è abbastanza per me.

In una delle tue prime foto ('Louisville 1986'), si vede Muhammad Ali che firma un autografo per due bambine. In una delle tue ultime foto, invece, hai ripreso un paesaggio deserto, avvolto nella nebbia mattutina. Vuol dire che ti stai muovendo verso un paesaggio pittorico, una realtà totale, più disincarnata, senza figure?

Ti riferisci alla mia serie attuale e continua 'Limehouse Reach'. Non ho mai pensato a me stesso come un fotografo paesaggista e ho sempre detto che preferisco sedermi nel paesaggio e contemplarlo piuttosto che cercare di metterlo in un piccolo rettangolo.

Ma alla fine del 2016 abbiamo lasciato New York e ci siamo trasferiti nella nostra casa sul fiume Tamigi a Londra. Sono stato immediatamente sbalordito dalla luce, dall'aria e dall'acqua in continua evoluzione del fiume. Cosa posso dire? Sono un fotografo e per la prima volta nella mia vita ho iniziato a studiare il paesaggio che ho di fronte ogni giorno – e ogni notte. Sono particolarmente attratto dalle nebbie, dalle nebbie, dalle tempeste, dalle nuvole e dal crepuscolo piuttosto che dai giorni luminosi e illuminati dal sole. Sono più transitori e fugaci e più difficili da fotografare. Sono anche ispirato dai molti pittori che ho studiato all'università, in particolare Turner e Whistler che davvero hanno fatto i loro disegni e quadri a un centinaio di metri da dove viviamo, e Constable che è stato anche attratto dai cieli drammatici dell'Inghilterra.

Nel tuo libro Storie brevi, il catalogo della mostra Mannheimer Kunstverein, ci sono solo pochi soggetti sorridenti. Gli uomini e le donne ritratti sono generalmente imbronciati, distratti e ritirati. Si può dire che tu voglia rappresentare l'alienazione moderna?

Questo perché è così che la maggior parte di noi appare per strada. Siamo sprofondati in noi stessi mentre andiamo da un posto all'altro. Certo, le persone ridono e sorridono, ma normalmente non lo fanno. Fotografo quello che vedo. Non so se rappresento qualcosa di più. Al massimo, le mie scelte sono determinate dal mio umore in quel momento. Tutti noi riveliamo i nostri stati psicologici nel nostro lavoro. Forse non in un unica fotografia, ma se guardi più fotografie fatte in un determinato periodo da una persona, puoi leggerci cosa sta succedendo nella sua testa.

Ad esempio, circa tre mesi dopo il mio trasferimento a Londra nel 1997, la mia amica Susan Lipper era in città e ci siamo ritrovati. Le ho portato i miei provini più recenti per mostrarle i miei ultimi lavori. Lei li ha esaminati e ha detto: 'Richard, ci sono alcune immagini molto belle qui, ovviamente, ma soprattutto quello che mi stanno comunicando è una sensazione di distacco, rabbia e alienazione'. Ho detto 'sì, questo riassume tutto'.

Sebbene ci siano spesso delle figure al centro delle tue fotografie, molti dei titoli si riferiscono a cose come un ombrello, un ombrellone, un taxi, un poster, un telefono Blackberry, ecc. In una foto 'italiana', anche l'attenzione è spostata dall'essere umano soggetto all'anteriore di una “500”, la piccola city car Fiat compatta.

I titoli sono quasi sempre del tutto irrilevanti nelle mie fotografie. Il loro unico scopo è differenziarli da un'altra fotografia scattata nello stesso luogo. Trovo titoli quasi sempre pesanti e inutili con le fotografie di strada. La maggior parte delle volte in realtà limitano ciò che ho colto con lo scatto, soffocandolo in una ragnatela di parole.

Hai scelto di nominare alcune delle tue serie con colori, 'rosa', 'rosso', 'giallo', ecc. Puoi spiegarci perché?

Stessa risposta di cui sopra. Se ho fatto dieci fotografie alla Easter Parade di New York, voglio differenziarle nella mia mente con un semplice tag. Con le fotografie a colori, se c'è un oggetto predominante di un certo colore, come un cappotto giallo, un abito rosa o una cravatta rossa, quella è l'etichetta.

Hai anche assistito a movimenti di protesta sociale come 'Occupy Wall Street'. Credi che la fotografia possa contribuire alla rivoluzione della coscienza? E se sì, come?

Non sono veramente sicuro. Sicuramente il fatto che oggi tutti abbiano in tasca una macchina fotografica/videocamera ha cambiato il modo in cui vediamo la polizia e la giustizia. L'omicidio di George Floyd da parte di un poliziotto sarebbe passato inosservato e impunito se non fosse stato registrato da una donna forte con il suo iPhone che registrava l'intera faccenda. Questo sta accadendo in tutto il mondo poiché coloro che perpetrano violenze e ingiustizie non possono fingere che non sia accaduto o che sia stata colpa della vittima. Il movimento mondiale Black Lives Matter non sarebbe esistito senza questo. È molto più difficile per la gente comune fingere che vada tutto bene e che questo non accada sempre.

Ma una fotografia individuale? Sono molto meno sicuro. Quando ripenso agli anni '60 (sì, sono molto vecchio e li ricordo bene) c'erano alcune fotografie incredibili che mi sono rimaste nella mente della guerra in Vietnam e delle proteste contro di essa. La bambina nuda che scappa dal villaggio in fiamme di My Lai e, dall’altra parte, la studentessa sotto shock e terrorizzata piegata sul corpo di uno studente morto che protestava, assassinato da un nervoso membro della Guardia Nazionale in Ohio. Più recentemente, conosciamo tutti la fotografia del giovane con le borse della spesa in piedi davanti ai carri armati in piazza Tien An Men a Pechino. Ma questo ha fermato il massacro avvenuto quella notte o l'omicidio di migliaia di persone quando il movimento è stato schiacciato? Ci sono molte altre singole immagini che rimangono con noi, ma cambieranno in mondo? Mi dispiace dire che non credo che lo faranno.